Ceramic injection molding stands at the convergence of ancient material science and modern manufacturing precision, a process that transforms raw ceramic powders into components shaping industries from aerospace to medical devices. Walk into any advanced manufacturing facility and you will witness a quiet revolution, where materials once shaped only by hand now flow through sophisticated machinery with tolerances measured in micrometres. This transformation has democratized access to complex ceramic geometries, making possible devices and products that previous generations could scarcely imagine.

Understanding the Process

The journey of ceramic injection molding begins with powder, the fundamental building block of ceramic manufacturing. These powders, ground to particles measuring mere micrometres across, possess properties that make them simultaneously promising and challenging. Ceramics offer hardness surpassing most metals, chemical stability resisting corrosive environments, and biocompatibility enabling use within the human body. Yet their brittleness and high melting points have historically limited manufacturing options.

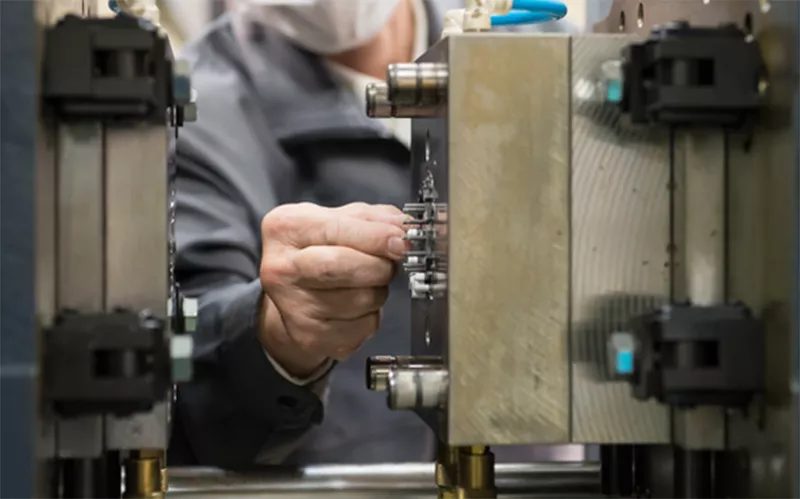

Ceramic injection molding circumvents these limitations through an ingenious workaround. The ceramic powder is mixed with thermoplastic binders, creating a feedstock that flows like conventional plastics when heated. This mixture can be injected into moulds under high pressure, filling intricate cavities and forming complex shapes impossible to achieve through traditional ceramic forming methods such as pressing or slip casting.

The Manufacturing Sequence

The process unfolds in distinct stages, each demanding careful control:

- Mixing ceramic powders with organic binders to create homogeneous feedstock

- Heating the feedstock until it becomes fluid and injectable

- Injecting the material into precision moulds under controlled pressure

- Cooling the moulded parts until the binder solidifies, holding the ceramic particles in place

- Removing the binders through thermal or chemical processes

- Sintering the parts at high temperatures, fusing ceramic particles into solid components

This sequence transforms powder into precision, but each step carries risks. Incomplete mixing creates weak spots. Improper injection leaves voids. Rushed debinding causes cracks. Yet when executed properly, ceramic injection molding produces components with properties matching or exceeding those made through traditional methods, whilst enabling geometries previously unattainable.

Singapore’s Manufacturing Landscape

Singapore has emerged as a significant centre for advanced ceramic manufacturing, leveraging its position as a hub for precision engineering and medical technology. The nation’s ceramic injection molding sector serves diverse industries, from electronics requiring insulating components to medical device manufacturers needing biocompatible implants.

“Singapore’s ceramic injection molding capabilities have developed alongside its medical device industry,” industry observers note, “with manufacturers investing in clean room facilities and quality systems meeting international medical device standards.”

The concentration of expertise creates opportunities for knowledge transfer and innovation. Engineers move between companies, carrying insights about process optimization. Suppliers develop materials tailored to specific applications. Research institutions collaborate with manufacturers, advancing both fundamental understanding and practical capabilities.

Applications Across Industries

The versatility of ceramic injection molding manifests in its breadth of applications. In medical technology, the process produces components ranging from surgical instruments to implantable devices. Ceramic’s biocompatibility and inertness make it ideal for long-term contact with human tissue. Hip joint components, dental implants, and surgical cutting tools all benefit from properties ceramic injection molding provides.

Electronics manufacturers rely on ceramic injection molding for:

- Insulating components protecting sensitive circuits from electrical interference

- Substrates supporting microelectronic assemblies

- Connectors maintaining signal integrity in harsh environments

- Heat sinks dissipating thermal energy from power devices

Aerospace applications exploit ceramic’s high-temperature stability and low weight. Turbine components, sensor housings, and structural elements withstand conditions where metals would fail. The automotive industry increasingly turns to ceramic injection molding for sensors, insulators, and wear-resistant components as vehicles incorporate more sophisticated electronics and emissions control systems.

Quality Challenges and Solutions

Yet ceramic injection molding remains demanding, requiring vigilance at every stage. The debinding process, where organic binders are removed before sintering, proves particularly critical. Remove binders too quickly and thermal stresses crack the part. Proceed too slowly and production becomes economically unviable. Manufacturers develop debinding schedules through careful experimentation, balancing speed against quality.

Sintering presents similar challenges. Parts shrink approximately 15 to 20 percent during this stage as ceramic particles fuse together and residual porosity disappears. Predicting and compensating for this shrinkage requires sophisticated modelling and extensive testing. Dimensional accuracy depends on maintaining uniform temperature throughout sintering cycles, necessitating precisely controlled furnaces and careful part placement.

Economic Realities

The economics of ceramic injection molding favour volume production. Initial tooling costs for precision moulds represent significant investment, often tens of thousands of dollars. These costs become viable only when distributed across thousands or millions of parts. For low-volume applications, traditional ceramic forming methods often prove more economical despite their geometric limitations.

This economic reality shapes which industries adopt ceramic injection molding. Medical device manufacturers producing thousands of identical implants find the process attractive. Electronics companies requiring millions of identical insulators benefit enormously. Custom architectural ceramics or artistic applications typically cannot justify the tooling investment.

Future Trajectories

Advances continue expanding ceramic injection molding capabilities. New binder systems enable faster processing and cleaner debinding. Improved feedstock formulations increase the maximum ceramic content, producing denser final parts. Computer modelling predicts shrinkage and distortion more accurately, reducing trial-and-error cycles during product development.

Additive manufacturing technologies begin complementing traditional ceramic injection molding, enabling rapid prototyping before committing to expensive tooling. This hybrid approach reduces development timelines and costs, making ceramic components accessible to smaller manufacturers and niche applications.

Conclusion

The transformation of ceramic powder into precision components reflects broader patterns in modern manufacturing, where ancient materials meet contemporary processes to serve emerging needs. From surgical theatres where implants restore mobility to electronics enabling global communication, the products of ceramic injection molding touch countless lives. As technologies advance and applications multiply, this manufacturing process will continue bridging the gap between material properties and geometric complexity, enabling innovations we cannot yet envision whilst building upon techniques refined through decades of incremental improvement and practical wisdom gained through ceramic injection molding.